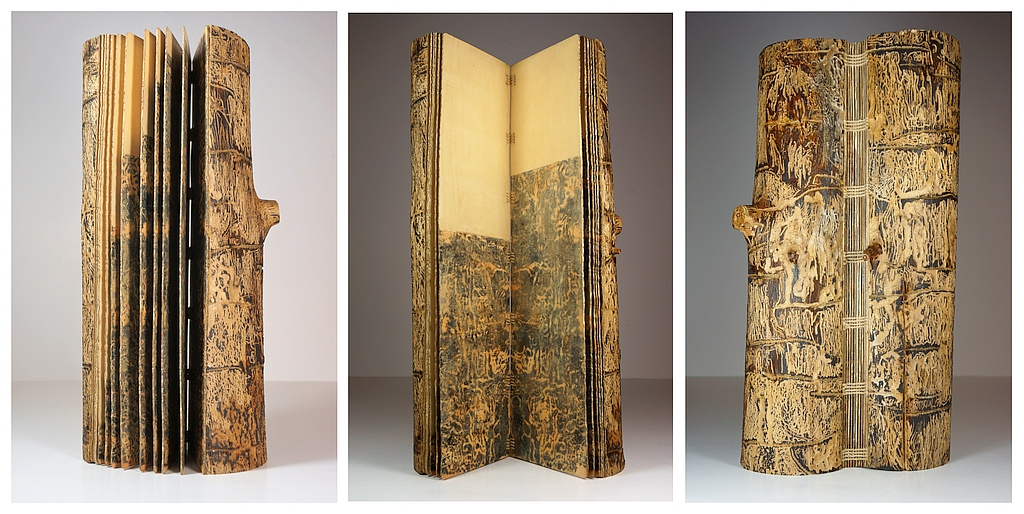

(“They” being my series of artist books made from bark-beetle-damaged wood and bark. Warning, this post is almost as long as the process!)

The Idea

I had the idea maybe as long as 4 or 5 months ago. I saw these paragraphs in the introduction to a textbook about bark beetles:

“Bark beetles play key roles in the structure of natural plant communities and large-scale biomes. They contribute to nutrient cycling, canopy thinning, gap dynamics, biodiversity, soil structure, hydrology, disturbance regimes, and successional pathways. Several species in particular can genuinely be designated as ‘landscape engineers,’ in that they exert stand-replacing cross-scale interactions.

In addition to their ecological roles, some bark beetles compete with humans for valued plants and plant products and so are significant forest and agricultural pests. These species cause substantial socioeconomic losses, and at times necessitate management responses. Bark beetles and humans are both in the business of converting trees into homes, so our overlapping economies make some conflict of interest inevitable.”

Kenneth F. Raffa, Jean-Claude Gregoire and B. Staffan Lindgren, Natural History and Ecology of Bark Beetles, Introduction to Chapter 1 Bark Beetles, Elsevier, 2015.

I started thinking about how I could invoke this competition for resources metaphorically. I’d collected some particularly handsome beetle galleries on medium-size branches in the Wenatchee National Forest. And I’d been reading one of Diana Six’s papers on the obligate mutualism of certain fungi to bark beetles – the beetles carry the fungi from one tree to another and the fungi convert some of the elements the beetles need to digest tree wood. Certain species leave a calling card—a greyish tone from the sapwood toward the heartwood, called “blue stain.”

Procuring Materials

I asked a Montana friend who used to manage a timber mill if he could get me any of this wood as dimensional lumber. That took a while, as not every supplier bothers to carry it, since it is not popular in appearance and may have the holes of other kinds of beetles. I didn’t need very much, so it wasn’t hard to ship it to me in Seattle.

I received the dimensional lumber about 10 weeks ago.

Laying Out the Cut

I decided to interpolate the branch shape to the 12-inch length of 1×4 over 16 spreads, or 34 pages, counting the inside front and inside back. I did the drawing in Inkscape and had it laser-cut with 36 binding holes, 9 groups of 4, and included those 1 mm holes in the drawing. Over time, I’ve developed a method for making these interpolations successfully.

I had some leftover 1/8” Baltic birch plywood from a previous project, so I laid out the cuts to fit it. It probably took me 2 days to make the drawing and its imposition onto the wood sheet. Then it turned out my usual local supplier, Fremont Laser & Design, had changed ownership and moved and was just getting started up again. So that took a little time, too. It was cut about 4 weeks ago.

Prepping the Materials

Oh yeah, there’s also soaking both the branch and the plank in Minwax wood hardener. I do that for several reasons: I once heard a story from a curator about an artist’s “organic” work on display from which emerged an army of live insects. So I want to be sure anything still in there is quite dead. Plus it helps stabilize the wood and prevent any further checking or cracking. And there’s the time I sit in the driveway cleaning the frass out of the galleries with an old toothbrush… So a couple of hours there.

Page Graphics

I faced the problem of what I wanted to show on those pages. They looked good by themselves, but I felt I needed to underline the meaning more strongly. I decided to morph an image of the branch into an image of the dimensional lumber, with each gradually taking over from the other over half the book’s pages. That is, in the first half of the book the bark beetle galleries take up more and more of the page—the beetles are winning; then the lumber becomes an increasing proportion of the page—the humans are competing.

This turned out to be a lot harder than I would have guessed. It was no big deal to photograph the dimensional lumber. But it took me several tries to figure out how to create an image of the branch (which is only ~2 inches wide) that I could use across all the different page widths. I knew I needed to “unwrap” the texture of the branch onto a 4”-wide rectangle. The method that finally worked was to stand the branch up on a lazy susan where 180-degrees were marked off in 22.5-degree segments. I set a camera on a tripod in front of the lazy susan, took photos at each 22.5-degree rotation, then used Microsoft Research’s Image Composite Editor to stitch them together. There went another few days….

I tried several different apps for morphing one image into the other but wasn’t satisfied with the image quality of any of the video morphing ones. I finally used the animation plug in for GIMP. But I had to figure out the proportions in pixels to have the correct transitions from one texture to the other, as well as how to fade one image into the other, since I didn’t want a harsh line between them.

And of course, with 20 layers, the file was huge and gave me all sorts of computer fits and starts. I finally got it to work, painfully exporting the image graphic for each page, front and back–66 in all.

Then I remembered the spreads needed to face each other, i.e. the image on the left-facing page would be flipped horizontally with respect to the right-facing page. However I could do this in page layout software… There goes a week.

I sent a PDF file to my partner’s 11 x17 office laser printer, with two of my book pages on an 11 x 17 sheet, but the prints weren’t as vivid and sharp as I had hoped. It turned out my own printer with high quality paper was better. So I re-laid it out on legal size paper, which is the largest I can print in my studio. Then I realized if I was going to use a laser print transfer method, I’d have to flip all the pages back the other way, since the print needed to go toner-side down onto the wood pages.

I also decided I wanted to include the text quoted at the beginning, so that meant going back into each image file of all the pages to add the text. And that the text would have to be reversed. There goes another week…

Laser print transfers for each page

OK, then the process becomes even more laborious. I coated both sides of each wooden page with acrylic gloss medium—two coats, a dry thicker one and a half-water, thinner coat to even out any rugosities. That’s 80 coats in all. Then I do the same thing with all the prints, 80 more. Then I use the same gloss medium to glue them together. I only made one sequence mistake, but it’s not very obvious, so I can live with it.

And speaking of tedious, after the prints-glued-to-wooden-pages dry for 24 hours under weights, the next step is to dissolve the paper off the back of the print. In my experience this usually takes at least three passes. In the first pass I run a sponge over the back of the paper and let it sit for a moment. Then with rough-fingered gardening gloves on, I begin rubbing the paper off. (I have learned to wear gloves, because I have previously rubbed the fingerprints off my fingers, making it difficult to log into my phone!). Once it dries, it’s easy to see how much paper is left to dissolve, and the second pass gets most of it off. But there is always still another bit of white fog after they dry, meaning there is still more paper to dissolve. And you have to be careful – if you rub too hard, you will tear or pull off the thin film of toner embedded in acrylic medium.

Trimming any excess film off is also nerve-wracking, because you don’t want to nick the wood and have light spots interfere with the handsome laser-cut edges. This proved to be quite difficult to do on my interior interpolated holes.

Then I coated each page with wax medium and let it dry. This acts as a sealing varnish that, unlike most other varnishes, won’t stick to itself since the book is usually stored closed. All in all, the coating, transfer, and varnishing phase takes another week.

The best way to see how this came out is in this video: Bark Beetle Book Vol. XXXIV page animation.

Binding

Finally, it’s time to bind the pages. I had included those 1 mm holes in the laser-cutting. Why did I include so many?!? Why did I make them so small!?!? In the binding method I used, modified Coptic, each station or hole requires its own needle. I didn’t have 36 needles that would fit into the holes with an eye large enough to accommodate my hand-dyed, 3-ply Kevlar thread. I had about 20 needles the right size and tried dipping the ends of the rest of the threads into glue to stiffen them, so they could act like shoelace aglets, but it was too slow and frustrating to get through the holes and wrap back around the stitches without needles. So several trips two different stores to acquire the right size needles.

At last I began binding, back to front. But not only did it take a long time to go over/in/out/wrap-around-the-stich and pull-through each of 36 stations, but when I coated each page with multiple layers of gloss medium, all the little sewing holes had become stopped up with acrylic. I had to take a nail and pound out each hole before I could sew the page.

Worse, by the time I got to the middle of the book and measured my remaining thread, I knew I hadn’t calculated the length of thread required correctly. My fall-back strategy was to begin binding front to back with new thread to meet and interlace in the middle. And of course I had to dye, dry and separate more thread. Two more weeks. And then…

Finally done!